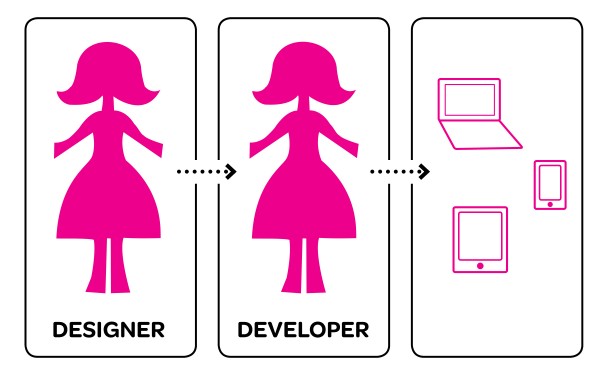

We live in an incredibly complex digital world. My new iPhone can do what?! I can collaborate online with how many people at once?! Despite this exciting features-based wonderland, many designers retain a rather dogmatic approach when designing for the screen. Why do we call webpages “pages?” Why does the navigation have to be at the top of the screen? Why do we design as if the screen space was only two-dimensional when we might simulate depth?

Before I alarm any user experience buffs, let me state that there is value in consistency; in providing the user a familiar visual language with consistent behaviors. I am advocating that we push past the 2D, print references that exist in online spaces and really explore what these spaces have to offer in terms of design and experience.

Exploring vs. Prototyping

Rapid prototyping when designing for interaction on screen allows for quick user feedback. There is an abundance of great material available about prototyping, but this is not about that. Exploring is not about determining function; it is about speculating and thinking through making. I’d imagine that when most designers are assigned a web project, they begin sketching — analog or digital — inside of little rectangles. Then perhaps a narrow bar appears to house the navigation. This approach often gets the job done, but maybe it’s time to try something new. Time to have a little fun. I propose an iterative 3D sketching method unbeholden to existing screen-based conventions.

Old Tools, New Tricks

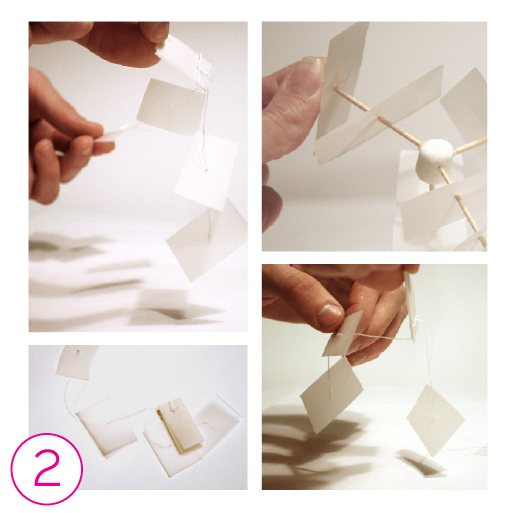

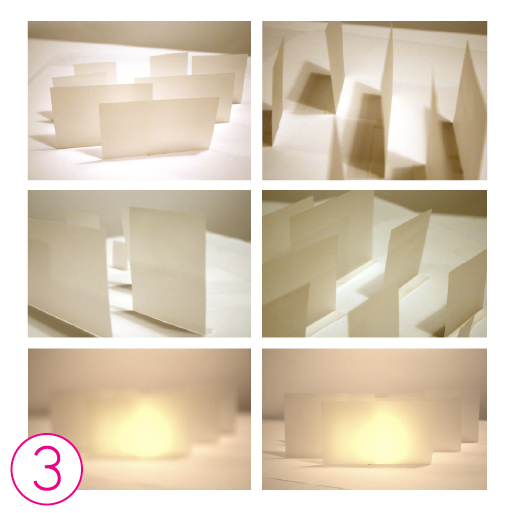

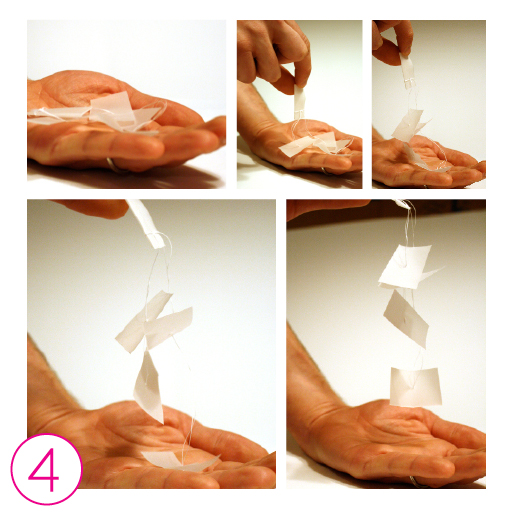

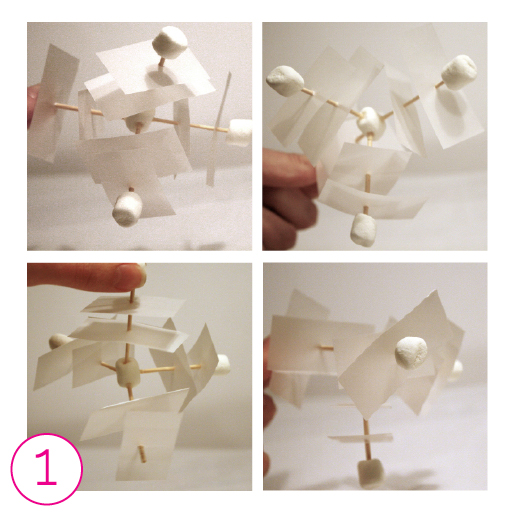

Much before you get to prototyping stages, there is an opportunity to reassess what an online space make look and feel like. I typically will focus on one aspect of my larger design problem, ex: If the webspace will provide research tools for teens, what might the photo search look like? Before I get too far ahead into thinking what something should look like, I grab some low stakes materials and begin building. Marshmallows, tooth-picks, string, boxes, vellum, anything you have laying around your house will work. What is important is that you brainstorm while making, reflect while making, and think while making. Don’t worry about the logistics of actually building a functionally finished artifact. (Programmers: I am pulling on bulletproof vest now). By sketching in 3D, you automatically free yourself of the limitations imposed by sketching with pen and paper. If you allow yourself the ability to build something with dimension, you will discover new ways of seeing online space.

The Beauty of Abstraction

Why keep everything so open, so abstract? By keeping your materials very simple and non-representational, you may project a variety of possibilities onto each 3D sketch. By holding and interacting with the sketches and running through various scenarios, you will discover new ways for the user to interact online. The abstraction allows you to talk about your loose ideas with others in a more tangible way. You avoid “air-comps” and give people something to react to.

Examples of self-imposed questions, regarding an online search:

1) What if images could be categorized similar to a library; fiction, non-fiction, biography, etc?

What if each radial represents a different trusted source?

2) What might a credible search feel like? Is it stiff and still or light and airy?

3) What if you could look behind an image to see more information, while still seeing other comparative images?

Does visual crispness imply something that blurriness does not?

4) Could online searching be like digging through a pile of images tied together with strings?

Could you approach images from different angles to reveal additional information?

quick tips

• Turn off your computer

• Raid your kid’s craft box or the pantry

• Brainstorm WHILE making

• Reflect WHILE making

• Play with the ‘finished’ 3D sketch and reflect about the implied possibilities

• Talk about it with someone